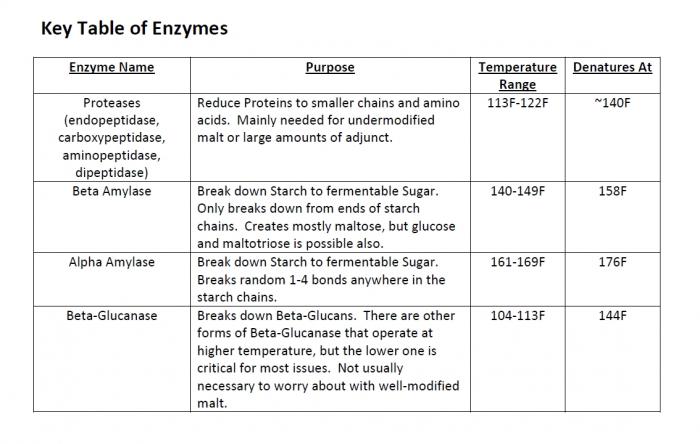

Beta enzymes denature at around 158 degrees.

I guess I had alpha and beta mixed up................... After reading your post, I did a bit more reading....... I thought beta was not destroyed until a higher temp. The term used is "deactivated". I don't think that means the same as destroyed. I would presume that when the temp drops back into range it is "reactivated". The term "deactivate" suggests that it simply quits working, as opposed to "denatured" which would imply a permanent chemical change. The literature is not clear on this.

In support of your assertions, I recently did a mash at 162, and the result was a not highly fermentable brew..... which was the goal, but I never dropped the temp back into the beta range. My next brew will be a 2% Mosaic Rye Wit... mashed at 152, but after that, I'm going to try a pale ale (2.5 gallon) starting the mash high...... About 162, and after half an hour or so, pull the insulation from around my pot (foam and blankets), and allow it to drop down below 150 (maybe help with cold water), and hold it there for an hour or so. This should allow me to see what happens with OG and FG.

I don't personally believe that either alpha or beta is "denatured" until around 170. Charts showing mash temps and attenuation would tend to support this.

fermentability [Narziss, 2005]:

Temperature 140ºF (60ºC) 149ºF (65ºC) 160ºF (70ºC) 167ºF (75ºC)

attenuation 87.5% 86.5 % 76.8% 54.0 %

The only way to draw a meaningful conclusion is to try it by brewing two brews identical except in the mashing schedule. The hydrometer readings should more or less tell the tale.

H.W.